Debut Novel Renegade coming soon!

The Art of Effective Worldbuilding: Lessons from the Continent of Orbis

C. Pintilie

11/5/20254 min read

Worldbuilding is the skeleton beneath every great story. It’s what makes a reader believe in your fiction long enough to forget it isn’t real. But “building a world” isn’t about dumping maps and lore into your reader’s lap; it’s about crafting a living, breathing ecosystem of history, geography, and human (or non-human) complexity that feels inevitable.

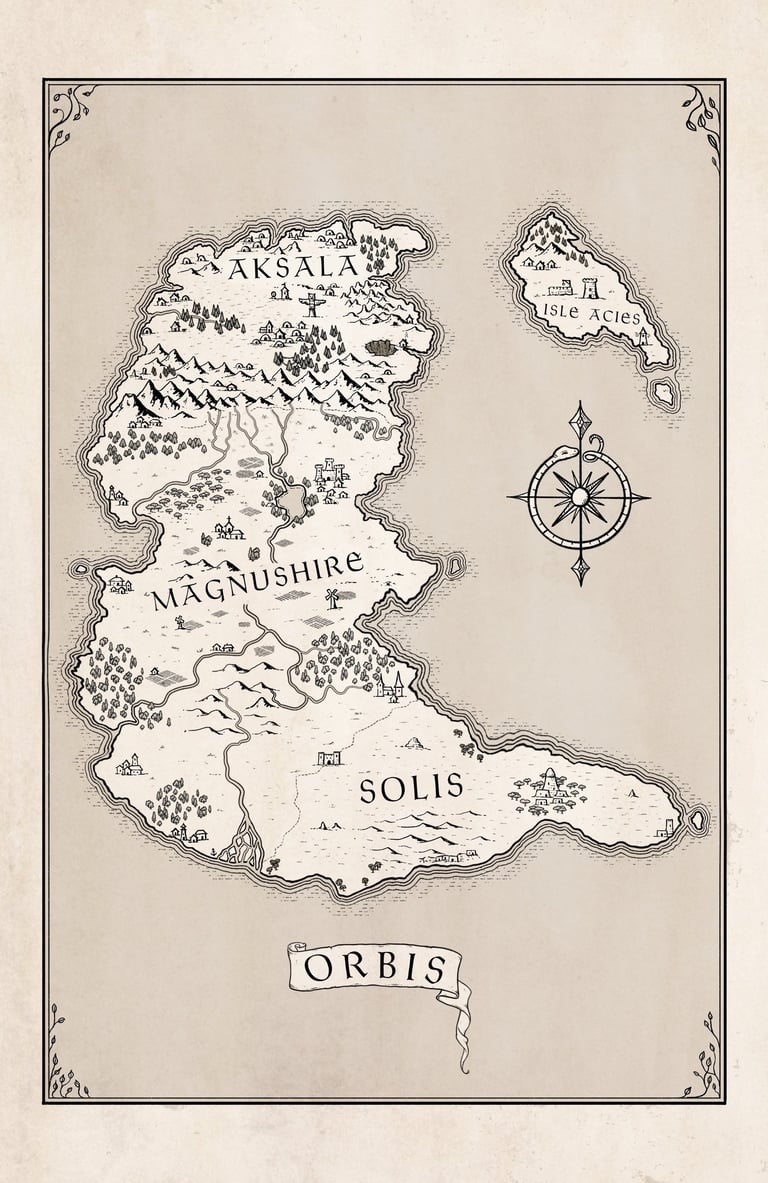

Let’s talk about how to do it right—using my own world, Orbis, as an example.

🌍 Step 1: Start with Land; Geography Shapes Civilisation

Every civilisation is a product of its landscape.

In Orbis, the world is split into three major continents, each defined by its environment:

Aksala: A frozen tundra of ice mountains and nomadic tribes. Life here is built around survival, endurance, and kinship. The terrain dictates belief systems that glorify the ancestors and spirits of the mountains.

Magnushire: Verdant forests, swamps, farmland, and sprawling cities. Its people are agrarian, intellectual, and class-based—a society where knowledge and wealth grow in tandem with the crops.

Solis: A searing desert continent cut off by natural barriers. Its people have adapted to scarcity with precision, ritual, and resilience. Water is currency. Shade is status..

Each landscape determines not just what people believe, but why. That’s the key to authentic geography in worldbuilding—let the terrain tell the story

💧 The Rule of Water

Follow the “rule of rivers.” Water flows downhill—always. It collects in lakes or seas. Civilisations rise near fresh water, not in random places on a map. If you want your readers to believe your world, don’t place a city in the middle of a desert without a reason—perhaps a hidden aquifer, or a trade hub around a rare oasis.

In Solis, that’s exactly the case: ancient cities cling to underground rivers called veins, which both sustain and imprison them.

⚔️ Step 2: Think Like a Historian — Empires, Wars, and Legacy

A believable world has scars. Empires rise, collapse, and leave behind ruins, hybrid cultures, and contested borders.

In Orbis, Magnushire once tried to colonize Solis, lured by tales of gem-rich sands. The invasion failed—not because of heroism, but because of logistics: supply lines couldn’t survive the heat. Centuries later, remnants of that failed empire still exist in the form of loanwords, hybrid deities, and bastardized dialects.

Your world’s history should work like sediment layers: each generation adds a new layer without erasing the old. Don’t just invent wars—consider their consequences.

Who gained power? Who was displaced? What cultural trauma lingers in songs, idioms, or superstition?

🗣️ Step 3: Let Language Be a Living Fossil

Languages evolve like rivers—they branch, merge, and erode with time.

In Aksala, the tribal tongues are consonant-heavy, mimicking the sound of cracking ice and sharp winds.

In Magnushire, older dialects persist in rural villages, while the cities use a smoother, Latinate trade tongue.

Solis languages are rhythmic and minimal, shaped by oral traditions where every word must earn its breath.

You don’t need to invent full conlangs. Just imply linguistic depth—through naming conventions, idioms, and syntax.

For example, a Solian might say, “The sun hides its face,” instead of “It’s cloudy.”

That phrasing reveals cosmology, not just climate.

🏛️ Step 4: Macro vs. Micro — Build the Skeleton, Then the Skin

Macro worldbuilding deals with large-scale systems—continents, nations, empires, religions, magic, trade.

Micro worldbuilding zooms in—one tavern, one flag, one myth told to a child.

Start big. Build the logic of your world: how do geography, resources, and climate influence politics and trade?

Then go small. Show how those systems shape daily life.

In Magnushire, nobles wear leaf-embroidered coats as a status symbol. Why? Because greenery is wealth—the mark of fertile land. That’s micro-detail born of macro-context.

🏴 Step 5: Symbols, Flags, and Faith — Culture in Conor

A world’s identity lives in its symbols.

Every nation, clan, or faction should have a visual language: colours, sigils, and patterns rooted in meaning.

Aksalan tribes carve their sigils into bone instead of fabric, since cloth freezes and tears in their climate.

Magnushire’s flag shows a golden stag leaping over a green field—a holdover from its first agricultural revolution.

Solis’ banners are strips of dyed sandcloth with patterns that shimmer in heat haze, symbolising survival through distortion.

Religions should follow similar logic: belief grows from need.

A desert people worship the sun because it both gives and destroys life.

A tundra tribe venerates ancestors because memory is survival in a place where the past freezes beside you.

🧍Step 6: Social Classes and Systems of Power

Class divides aren’t just about money. They’re about access—to safety, education, and choice.

In Magnushire, power stems from literacy. In Aksala, it’s lineage. In Solis, it’s control of water. Each form of hierarchy feels inevitable because it grows organically from environment and history.

When worldbuilding, ask:

What’s the ultimate currency here? (Water, gold, magic, reputation?)

Who decides truth? (Priests, kings, scholars?)

Who’s invisible—and why?

✍️ Step 7: Make It Personal

You don’t need to show all your world to make it real. The illusion of depth comes from specificity.

A passing reference to a half-forgotten festival, a weathered mural, or a regional insult can imply centuries of unseen history.

Readers don’t need your entire atlas. They just need to feel that it exists beyond the borders of the page.

🧩 Final Thought: Worlds Are Not Built, They’re Remembered

Effective worldbuilding isn’t invention—it’s discovery. It’s archaeology with ink.

When your geography dictates your politics, your history explains your myths, and your cultures contradict each other in believable ways, then you’ve built a world that feels alive.

Orbis works because it mirrors the logic of our own Earth—its empires, mistakes, migrations, and miracles.

And that’s the secret: every imaginary world is just a reflection of ours, seen through a different light.